More to Discover

Beneath Our Feet is the culmination of two intertwined strands of artist Leah Higgins life – a deep connection with textiles and a fascination with industry, how things are made and how things were made.

With a mother and grandmother who believed that a woman should always have ‘something on the go’, Leah was taught to stitch and knit from a very early age and learnt to use a sewing machine at age nine. As a teenager she made clothes for herself and her sister, later she made things for her husband, their children and their home. In her thirties she taught herself to pattern cut and helped to support her family by designing, making, and selling children’s clothes. For decades the results of her ‘making’ were practical, made for a purpose rather than made for the love of making.

This changed when Leah was introduced to patchwork and quilting. The bed quilts she made for her family were still practical, but they weren’t ‘necessary’. They were made with love, initially following other people’s patterns but eventually made to her own designs. She learnt to dye her own fabrics, completed City & Guild courses, and, in 2010, learnt to screen print. She started to print and dye all the fabrics she used. And slowly her work stopped being ‘hobby’ it became a passion, an obsession, it became her art.

Leah is not an artist by training. She studied Chemistry at Imperial College and worked as a development chemist before taking a break to have a family. She returned to university at 37 to study for her PhD in textile science. An intuitive understanding of how different textile behaved was enhanced by a growing knowledge of how different types of fabrics were manufactured and the role of chemistry in the different manufacturing processes. She went on to work in a technical role for an international floorcovering company based in an old cotton mill before establishing her own studio and working as an artist full time. The analytical nature of science, the efficient working practices demanded in a modern manufacturing environment and experience working with dye companies, designers and colourists underpin elements of her art practice today.

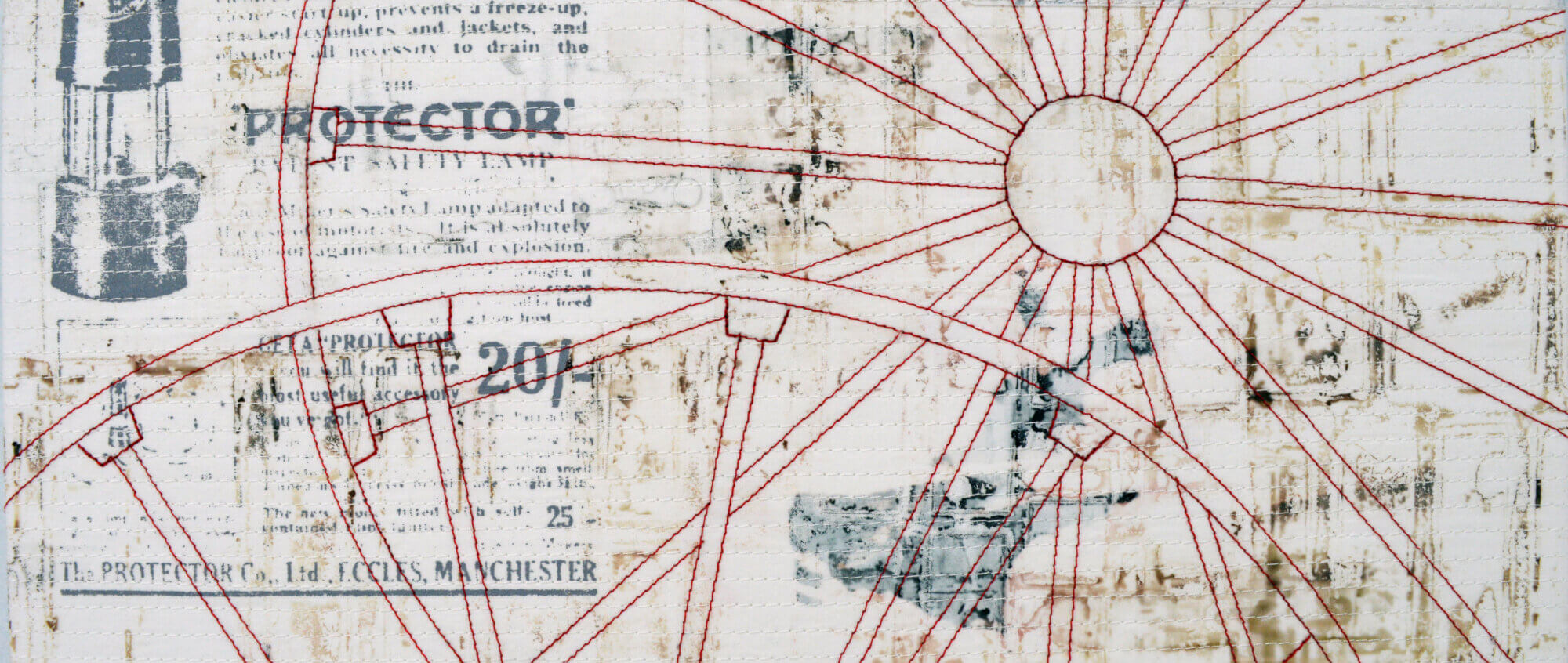

In her Ruins series Leah explores what happens to industrial buildings and industrial landscapes when those industries are left behind. She developed printing techniques that gave the type of mark and density of mark that these ideas needed. The early pieces were purely abstract but over time Leah introduced elements in her work that referenced specific industries. Ruins 9: Cottonopolis Revisited and Ruins 10: Salford Mills inspired purely by the cotton industry in Manchester. Ruins 12: Beneath Our Feet is inspired by the link between coal mining and cotton production in Manchester and references the Worsley Navigable Levels, largely built by the Duke of Bridgewater to increase production levels and to link his coal mines to the rail and canal network. In Ruins 13: Astley Green, Leah references the local coal mining museum which holds the only surviving head gear and engine house in Lancashire.

The history of the cotton and coal mining industries in Manchester and surrounding areas is inextricably linked. For two centuries they shaped the landscape and the lives of many. With over 100 mills in the city itself, Manchester was the commercial centre for the 2650 cotton mills that were operating in Lancashire by 1870. At its peak the Lancashire cotton industry employed nearly half a million people: most of them in the hulking red brick weaving and spinning mills. Most of those mills were powered by steam engines fuelled by coal. The proliferation of collieries within Manchester and further afield were connected to the mills by new canals and new railways. Alongside coal, some companies mined fireclay needed to make bricks for new mills and new homes and occasionally used to make decorative tiles and pottery.

Whilst the growth of the cotton and coal industries were intertwined, their demise followed different paths. Cotton production in Manchester declined rapidly during the late 19th and early 20th century. Many mills were destroyed but many survive today. The towering red, brick-built mills of the cotton industry still shape the landscape in Manchester and the surrounding towns. The wealth derived from cotton is still evident in many of our public buildings.

Coal mining continued to grow, driven by ever increasing demand for electricity. But a combination of cleaner, gas fuelled power stations, cheap coal imports and the increasing politicisation of the industry drove a dramatic decline in coal mining in the late 20th century. Hundreds of collieries closed; close-knit communities were decimated. Many are still blighted today. But unlike the cotton industry and cotton mills, coal mining and those industrial structures that once dominated so many lives and so much of the landscape in northern England were systematically erased. The pit heads, winding wheels and slag heaps all gone. Paved or grassed over.

As a child Leah spent her summers with her grandparents in a small village in Nottinghamshire. Calverton Colliery was two miles away and employed 1600 people in the area. The pit in Blidworth was four miles away. Family and friends worked down the mines; lived in Coal Board housing; had their lives cut short by bad lungs. Production at Blidworth stopped in 1989. It stopped at Calverton in 1999. Her children can’t remember driving past the pit heads and slag heaps. They were too young and now nothing remains.

In her Traces series Leah initially printed her fabrics in black and dark greys before removing nearly all of the colour, leaving a ghost of what was once there. In the ten panels exhibited as part of Beneath Our Feet she used site maps, images of miners tallies and old documents to reference specific collieries in Salford and Manchester. In The Cost of Coal she was inspired by Bold Colliery which was part of the South Lancashire Coalfield. The men and boys who worked at Bold produced coal for over 100 years but at a terrible cost. 70 men and boys lost their lives during that period. The youngest were only 14 years old. In The (Continuing) Cost of Coal (and Other Fossil Fuels) Leah has reworked a similar quilt to remind us of the cost to our health and the environment of our continued reliance on fossil fuels.

And finally in her Artefact series Leah is inspired by our relationship with man-made objects, especially those made with material taken straight from the earth and shaped into tools and decorative objects. Those objects which are collected and proudly displayed; those which are passed down within families; those that tell us about our past; and those that are lost to us. In the works shown as part of Beneath Our Feet she specifically references the vases and decorative tiles made by the Pilkington’s Tile & Pottery Company in the early 20th century. The Pilkington’s company was founded after an attempt at drilling two shafts found red marl clay rather than the hoped for coal. The company was sited to take advantage of the canals and railways built to service the rapidly expanding coal mining industry.

In Artefact 5 Leah references those vases that were hand painted using floral motifs by a small team of female artists and asks the question how do we respond today to the apparent sexism behind the flora motifs used by the female artists versus the historical motifs used by their male colleagues? In Artefact 6 she uses simple tile designs taken from the Pilkington’s archive to reference the scale of manufacturing. Made in multiples, should the tiles be classified as hand-crafted or mass manufactured? And in Pigment #1 Leah celebrates the wonderful, brightly coloured glazes developed by the Pilkington chemist Abraham Lomax. The development of these glazes were an early example of where science, in this case advances in inorganic chemistry, were applied to the art of the potter. And an appropriate subject for Leah, the scientist and artist to explore.

The artist is grateful to Stephen Wainwright for letting her use images from his wonderful website (www.suttonbeauty.org.uk) in the two ‘Bold’ quilts and to Duncan McCormick for helping her access the Pilkington’s Archive housed at Salford Museum and Art Gallery.

Sign up to the Salford Community Leisure mailing list and be the first to find out about our latest news, offers and forthcoming events across our services.